One of the many excellent and fun reasons to learn to fly is to visit new places by air. Taking your friends and family on an aerial adventure to a faraway location (or maybe just seeing their homes from above) is incredibly rewarding. But how do pilots navigate about the skies, and find their way to these destinations?

In this article, I’ll explain the basic air navigation principles you’ll be taught on a pilot’s license course, and what to expect from your navigational training.

The Basic Principles of Finding Your Aerial Way

There are no easy to follow road signs in the skies! Pilots must use compass and stopwatch to navigate, using a principle called deduced reckoning.

This principle states that if you steer a known speed and constant direction for a set amount of time, you’ll end up at a mathematically predictable location. For example: if you flew at one hundred miles an hour, for half an hour, you’ll have travelled fifty miles. If you used a compass to steer due north, you will end up fifty miles north of where you started – simple!

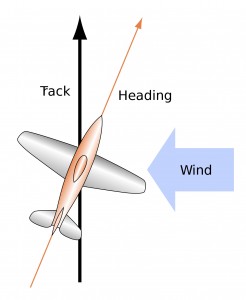

Since airborne winds will blow an aircraft off course, and change the speed it flies over the ground, you’ll also need to factor in wind strength and direction. The winds aloft are predicted with reasonable accuracy by those nice people at the Met Office, which can be used to adjust the calculations accordingly.

So, if you want to steer your aircraft from one place to the other, you can calculate the number of minutes you need to fly in which direction, for a given airspeed. This allows you to steer a desired track over the ground. This is the most fundamental air navigation principle. Everything else is refinement!

Learning to Navigate the Sky

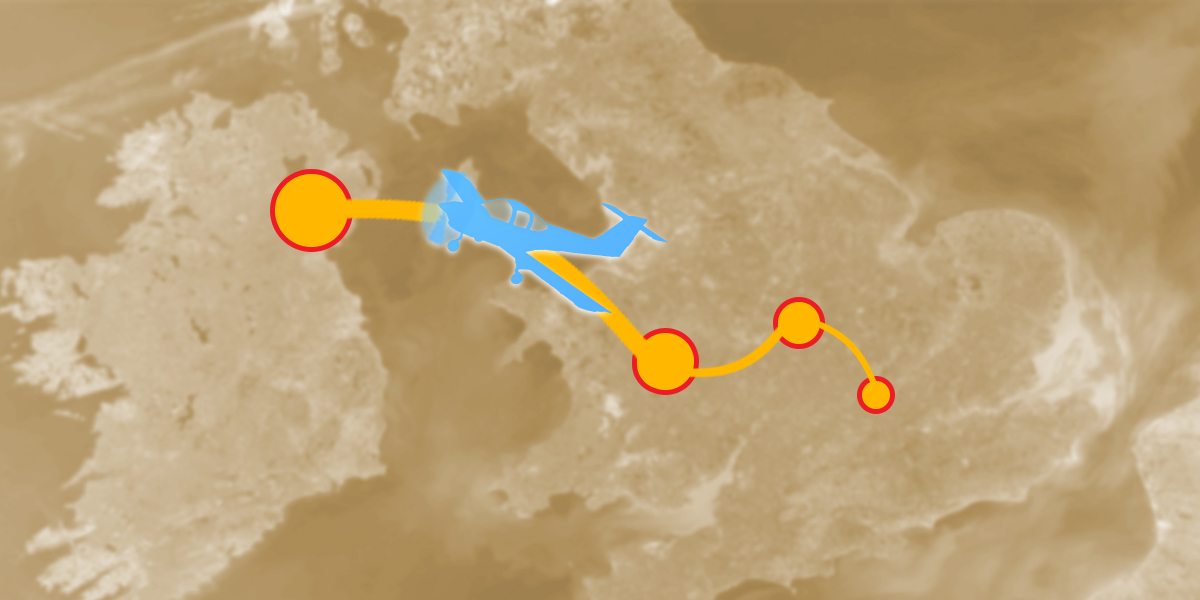

During your pilot training, you’ll be shown how to use an aeronautical chart (a large scale map, with the locations of airfields, towns and zones of controlled airspace) to plan the route to be flown. Routes are normally planned via a series of waypoints (normally ground features that can be easily identified from the air).

Using deep and dark piloty knowledge, a pilot will perform a series of calculations to produce a set of headings and timings to fly from waypoint to waypoint, and notes them down on a pilot’s log (termed a “plog”).

Each waypoint should ideally have at least three unique features, allowing the pilot to positively confirm that the aircraft has ended up where it should be. More than one pilot has misidentified one town for a similar (yet not identical!) place nearby, leading to navigational errors, and gentle ribbing in the flying club bar later on.

Having established that the aircraft has arrived at the correct waypoint, (or not!), any necessary adjustments are made to headings and timings, and the flight continues to the next waypoint.

Of course, in practice sometimes pilots will get lost (any pilot who claims they’ve never been lost tends to attract funny stares from other, more honest, pilots) so training on how to stop being lost is also an important part of the private pilot syllabus. It’s also worth noting that a good instructor will try and make sure that the first time you get well and truly lost occurs on a flight with said instructor on board…

Radio Aids

Whilst deduced reckoning is the core principle of finding your way about the skies, it’s not always feasible (for example, there are not many unique features over the sea or desert!) and can be limited in accuracy. Happily, ever since the Second World War, a succession of increasingly sophisticated navigational aids have been developed, which in an updated form today help pilots precisely plot their position.

Some of these aids are ground-based, and consist of a series of radio beacons at fixed locations. These transmit signals that an aircraft’s cockpit instrumentation can interpret to provide navigation information. In addition, GPS systems are becoming even more commonplace; a number of cheap and effective applications for GPS-enabled tablets and smartphones allow pilots to navigate with a very high degree of accuracy.

There are still a number of limitations – and, as with any computer aided navigation, it’s always good to have a manual backup. This is why basic navigation and using your plog are the first taught principles of navigation. In addition, a good pilot should always anticipate and think ten minutes ahead of the aircraft, so a good awareness of where the aircraft is heading and how long it will cover ground is essential.

Once you’ve mastered these techniques, the next part of training is deciding on exactly where you’d like to fly to. The UK boasts a number of marvellous destinations for private pilots – I wish you happy times in navigating to them!

Happy aviating!