Imagine being the passenger or driver of a car that is travelling at speed along a motorway below a sparkling bright blue sky. Then imagine that lovely blue sky instantaneously becoming a wall of grey, dull fog surrounding you on all sides. That is similar to flying into cloud in an aeroplane, and is why pilots must learn to fly using the instruments inside the cockpit, and without reference to the outside world.

In your car you might choose to slow down, put on some lights or, if the fog was bad enough, stop and wait for an improvement in the conditions. The luxury of stopping and waiting for better weather is not one that pilots flying in such weather have – nor should it be – as most aircraft are more than capable of being flown in such conditions.

On first looking, the average airliner cockpit can be overwhelming with an endless array of switches, screens and dials – but this selection of modern technology provides the pilot of an airliner with exactly the same information as that required by the pilots of smaller aircraft that may have fewer screens and perhaps a more retro look. The need for information about altitude, speed and direction has not fundamentally changed since the days of early aircraft.

Remember our flying in cloud? Knowing at what speed and in which direction we’re moving can help us to establish where we are, as long as we knew our position before going into that cloud. And that is the essence of instrument flying. It is nothing new; the first pilot to take off, fly and land an aircraft using instruments alone did so way back in 1929.

Remember our flying in cloud? Knowing at what speed and in which direction we’re moving can help us to establish where we are, as long as we knew our position before going into that cloud. And that is the essence of instrument flying. It is nothing new; the first pilot to take off, fly and land an aircraft using instruments alone did so way back in 1929.

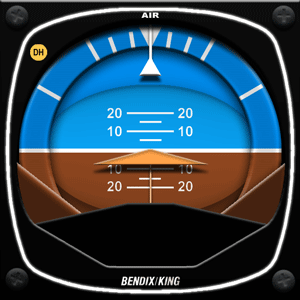

Most aircraft built since the 1930s have the same instruments arranged in a standard pattern called the T-arrangement. If flying in cloud could be achieved by looking at one instrument then it would be easy,  but in practice flying in low visibility requires constant reference to a number of instruments in order to maintain a safe altitude, at a safe speed and to travel in a safe direction.

but in practice flying in low visibility requires constant reference to a number of instruments in order to maintain a safe altitude, at a safe speed and to travel in a safe direction.

The T-arrangement made this easier.

The key instrument is the attitude indicator. In the middle of the top row of the T-arrangement, this instrument is the central element of a pilot’s scan. When flying in cloud the attitude indicator, sometimes also called an artificial horizon, replaces the natural horizon that the pilot would have seen and used to understand the relationship of the nose and wings of the aircraft to the horizon.

Other important instruments are the airspeed indicator, altimeter and compass. The compass works exactly like a normal compass that displays the direction in which the nose of the aircraft is pointing. This can be different from the direction in which an aircraft is moving or travelling over the ground due to the effects of being blown by the wind.

The altimeter and airspeed indicator derive their information using air pressure. A tube, usually on the front of an aircraft and called the pitot tube, grabs air and compares this to the air pressure on the ground and the pressure around the aircraft. This information can then be displayed on the instruments, letting a pilot know how high and how fast she is travelling.

So, putting the information gained from the attitude indicator along with that provided by the airspeed indicator, altitude shown on an altimeter and the direction of travel shown on a compass gives us everything we need to fly through cloud. The skill is in learning how to do that whilst also navigating and also to fly an aircraft in accordance with a set of rules to ensure that someone else flying through our cloud doesn’t hit us… because we wouldn’t see him coming in time to take avoiding action.

It is straightforward, and delightful, in clear weather to fly an aircraft with reference to outside visual clues such as the horizon, and to know our position using towns, buildings, roads and terrain features for navigation. It is also wise to maintain ‘separation’ from other aircraft enjoying the fine weather be they an airliner or smaller aircraft.

The Civil Aviation Authority, which writes the rules for flying in the UK, calls this Visual Meteorological Conditions (VMC) and sets the limits for how low cloud can be and what the horizontal visibility must be for such. These are called Visual Flight Rules (VFR). This is what flying is about and provides a pilot with freedoms to explore the sky and perhaps practice some aerobatics – but what it doesn’t mean is that a pilot can fly just anywhere.

In order to keep airliners and their passengers safe, there are Instrument Flight Rules (IFR) that create conditions that do so. IFR does not necessarily mean flying in cloud, but means that airline pilots can be assured that they are flying along lanes and travelling in areas where all the aircraft are fitted to a similar standard and ensures that separation mentioned above.

All airline flights are operated under IFR irrespective of whether the weather is blue skies or foggy – and in accordance with strict criteria. This doesn’t stop airline pilots looking out of their cockpit windows but it ensures that they fly safely even if nothing is visible. At all times Air Traffic Control will know who they are, where they are going and provide the airline pilot with navigation orders and advice… And if it gets really bad, certain airports have landing systems that will effectively provide an automatic pilot with enough information to land the aircraft without the pilot touching the controls.

VFR means one is on one’s own – but there is still a place for the pilot of a smaller aircraft such as a Cessna 172 to learn to fly using instruments as it generally leads to improved flying skills… and is always good to keep in one’s pocket for that day when the weather turns unexpectedly bad. Flying on instruments is good fun and another one of the skills of flying to master.

Safe flying!