History of Flight: In the beginning there was a monk…

Ancient history is dotted with accounts of folk taking to the skies in various whimsical ways, but if we decide to skip over the aviators who relied on magic or awesome flying horses, the first verifiable attempt came sometime around 1015AD. An English monk, Elmer of Malmesbury, got bored of all the incessant monking one day and, inspired by the myth of Icarus, decided to launch himself from a church tower, aided by a couple of bedsheets strapped to a pair of wooden-framed wings.

The prevailing wisdom at the time held that since birds seemed to do ok flapping their wings, a similar set-up ought to work for monks, or indeed anyone else who fancied a go. Two broken legs later, Elmer came to the conclusion that he probably should have built himself a tail too, though strangely he never quite got around to trying again. He wasn’t wrong – some form of tail would certainly have helped with keeping him balanced, but unfortunately that alone wouldn’t solve the problems arising from the pesky fact that humans, even malnourished mediaeval monks, are way too heavy to achieve flight through the strength of arm-flaps…

Over the following centuries, various would-be birdmen around the world continued to maim and kill themselves in the pursuit of that beautiful, flappy dream, and while none were successful at flying, you’ve got to admire their pioneering spirit. File under insane but awesome.

History of flight: Da Vinci’s flying machines

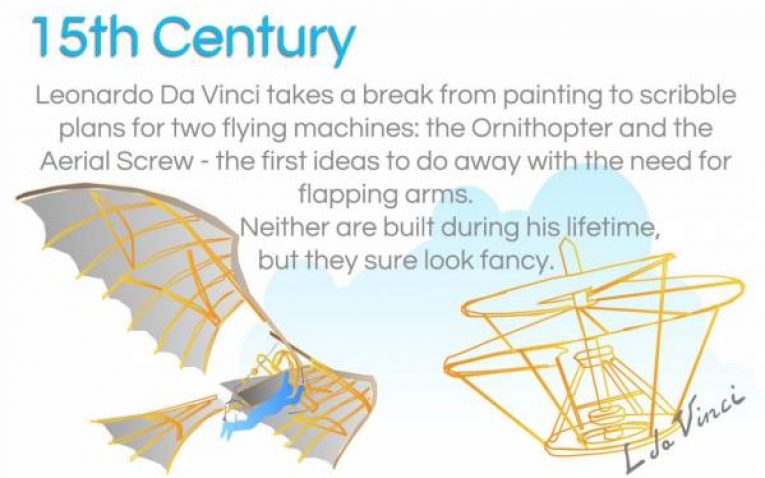

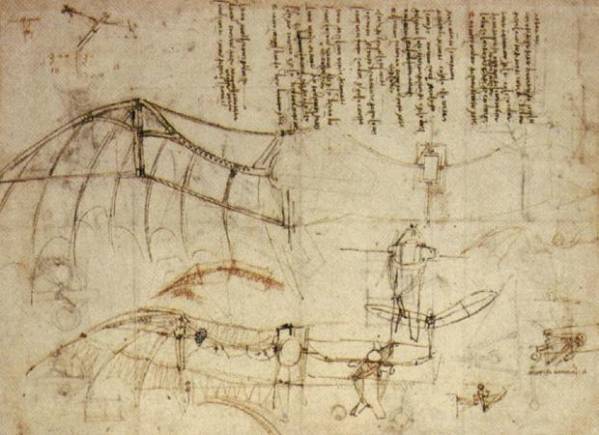

Moving on a few hundred years, we come to the Renaissance man himself, Mr Leonardo Da Vinci. Old Leo was perhaps the first to realise that, while it’s all very well to mimic the shape of a bird, the inescapable truth is that human arms are frankly far too measly and weak to ever flap hard enough to keep our flabby bodies airborne. Luckily, when he wasn’t busy painting smirky noblewoman, Da Vinci was something of an engineering geek, and he managed to find a spare ten minutes to sketch out designs for not one, but two whole beautiful flying machines.

The first, the Da Vinci ‘Ornithopter’, still carries some hallmarks of its bird-impersonating predecessors, though its shape actually owes more to the only truly flying members of our own mammalian family – the bats. The big innovation Leo made was to remove the responsibility for flapping from the shoulders of the pilot; instead hooking up a system of pulleys and gears to a set of hand- and foot-powered peddles – allowing for much faster and stronger wing-beats. Unlike poor old Elmer, Da Vinci was blessed with enough sense to keep him from ever actually testing his invention, but if he had, modern scientists think that, while it would need a wee bit of help to initially get airborne (jump off a tall tower, anyone?) it could possibly, maybe, no promises like, have achieved actual flight.

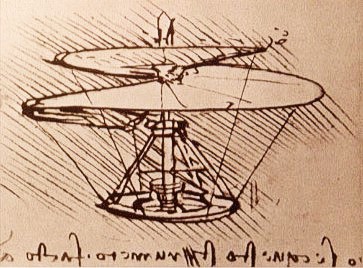

Leo’s second contribution to aviation is one that has had a clear influence on some of today’s most popular flying machines. The ‘Aerial Screw’ (nothing to do with the mile high club, get your mind out of the gutter) is the direct ancestor of the modern helicopter, and is the first time we see an  early incarnation of one of the key methods of flying propulsion – the rotary propeller. Rather than using the energetic flapping motion of wings to produce lift, this machine takes inspiration from the twirling of falling seedpods. As the name suggests, it’s essentially a giant helical screw attached to a platform, which Da Vinci imagined would hold the four men needed to power its rotation. As with the Ornithopter, the device was never built, and would probably never have been powerful enough to lift its human cargo, but if only he’d made the effort to invent an internal combustion engine to power it, this one might actually have worked. Tut tut. Bad form, Leo. Still, he did manage one or two other piffling achievements in his time, so we mustn’t grumble.

early incarnation of one of the key methods of flying propulsion – the rotary propeller. Rather than using the energetic flapping motion of wings to produce lift, this machine takes inspiration from the twirling of falling seedpods. As the name suggests, it’s essentially a giant helical screw attached to a platform, which Da Vinci imagined would hold the four men needed to power its rotation. As with the Ornithopter, the device was never built, and would probably never have been powerful enough to lift its human cargo, but if only he’d made the effort to invent an internal combustion engine to power it, this one might actually have worked. Tut tut. Bad form, Leo. Still, he did manage one or two other piffling achievements in his time, so we mustn’t grumble.

History of flight: Battle of the Ballooning Brothers

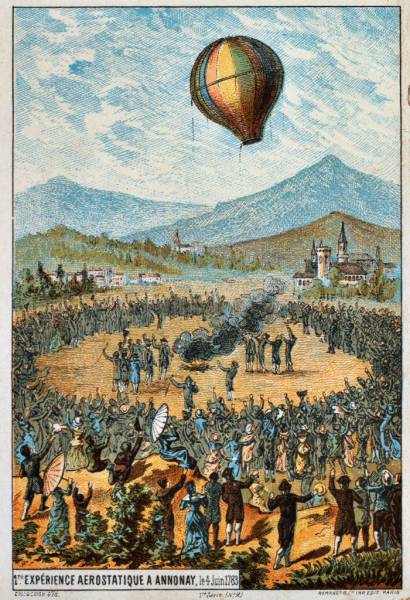

Our next stop along the timeline of people for whom jumping just wasn’t enough brings us to 18th century France and the Brothers Montgolfier, inventors of the ‘Globe Aerostatique’ or, as it’s known to us Limeys, the hot air balloon. In 1777, Joseph Montgolfier was chilling out in front of a fire, watching laundry dry (the height of light entertainment in the pre-internet age) when he observed a pillow catching a draft of hot air and billowing upwards. Awed by this magnificent sight he was immediately inspired to set about planning a practical application. Well… we say immediately. He actually lazed about for five years (laundry watching is a full-time hobby) before eventually getting around to building a small wooden frame clad in taffeta and setting it aloft with hot air from the fire. Now, none of this was particularly astounding, especially when we remember that the Chinese had already been using this exact technique to make little airborne firebombs for well over a thousand years by that time. However, it was what happened next that was truly impressive. Spurred on by the success of his tiny balloon, Joseph recruited his little brother Etienne to build a larger version. And into this glorious contraption, they placed… a chicken. Also a duck and a sheep. Seriously.

Fast forward another year or two, and eventually the first manned free-flying hot air balloon took to the skies over Paris, and the world watched in wonder as humanity finally achieved the dream of truly flying. Quite the milestone, and hot-air ballooning was briefly all the rage among moneyed Parisians, but the first incarnation of hot-air had barely taken off before it became, as with so many fashions of Marie Antoinette’s court, just so passé, darling.

Fast forward another year or two, and eventually the first manned free-flying hot air balloon took to the skies over Paris, and the world watched in wonder as humanity finally achieved the dream of truly flying. Quite the milestone, and hot-air ballooning was briefly all the rage among moneyed Parisians, but the first incarnation of hot-air had barely taken off before it became, as with so many fashions of Marie Antoinette’s court, just so passé, darling.

The big problem was that hot-air flight required the balloon to be filled whilst on the ground, and this meant that they could only stay aloft for as long as it took the air to cool down. Luckily, even as the Montgolfiers were taking their first flight, another set of French brothers were hard at work preparing to one-up their rivals with an invention that overcame this flaw. Only 10 days after the first manned hot-air balloon took flight, the first Gas-Balloon – designed and built by the Brothers Robert under the watchful eye of Professor Jacques Charles – embarked on its own maiden voyage, with Nicolas-Louis Robert and the Professor himself aboard. The big improvement over the Montgolfiers was in their choice of a lighter-than-air gas (namely hydrogen) to fill their balloon, allowing the craft to fly for longer and further. Gas ballooning quickly overtook hot-air in popularity, and remained relatively common right up until the twentieth century when the dawn of the airship took it to a whole new level.

Keep an eye out for part 2 of the Ground School History of Flight for the next stage in our timeline of the amazing evolution of human aviation!